If you’ve been suffering from unresolved back pain for a while, your doctor may have ordered an x-ray or an MRI to figure out why. Doctors order MRIs for a condition that’s been sticking around for a while or worsening.

Your x-ray or MRI may reveal a condition called lumbar stenosis, a condition where spinal openings have narrowed as a result of age or injury. This can result in pain and discomfort, but it doesn’t always mean surgery. Many people manage their lumbar stenosis conservatively through physical therapy.

If you’re looking for more guidance regarding back pain, book a session at any of JACO Rehab’s Oahu locations!

A Word On Imaging

X-rays and MRIs can be… scary! Not only are you surrounded by loud machines, but the fact that you even need imaging isn’t exactly encouraging.

Do not fear! Here’s what we know about imaging.

MRIs can be useful, but they’re not always necessary

MRIs can be useful in locating the problem if physical therapy isn’t working, despite adjustments in treatment plan. MRIs are more likely to be approved after six weeks of physical therapy, depending on insurance requirements. This is because MRIs are expensive. If conservative treatment is showing positive results, then you’re figuring it out without unnecessary imaging.

If you are having significant amount of pain, an MRI should not be your immediate goal. An unnecessary MRI can negatively impact how you view your condition because…

Not every imaging result applies to your condition

X-rays and MRIs can show multiple findings. That doesn’t mean that every single one of these findings is contributing to your symptoms.

In fact, certain results are common and aren’t inherently symptomatic.

Osteophytes (bony growths/calcification), narrowing of joint spaces, and “arthritic changes” are all terms that are often associated with painful conditions. But if you were to x-ray or MRI random people, most of them will have these findings and not even know it. Some of those results are normal, age-related changes—almost like developing wrinkles. It’s natural to have some changes over time.

So, if you see a list of medical terms and results in your imaging report, that doesn’t usually mean you have a lot wrong with you. Some of those findings may not even relate to your symptom presentation.

Imaging can be great tool to help you understand what may be causing your condition, but you should not be intimidated by results. Fear can be quite detrimental to your condition according to many studies in the ever-growing realm of pain science. (1)

Ask your doctor to clarify the findings if you have any questions.

What Does It Mean to Have Lumbar Stenosis?

The lumbar spine (or your low back) is subject to degenerative changes over time, just like any other part of your body.

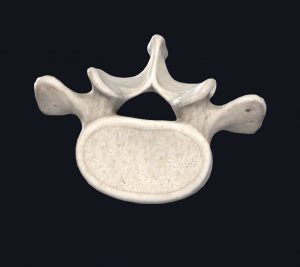

Your spine has holes and canals that house nerves. You can see them below, the spinal canal on the left, and the intervertebral foramen on the right.

Images courtesy of Complete Anatomy

These areas can narrow with age, most often in individuals >60 years old. That narrowing is given the term stenosis.

Lumbar stenosis is not always symptomatic. Narrowing doesn’t have to be painful just because it’s present. But it can be problematic if it starts to encroach on a nerve and cause inflammation.

Nerve inflammation from lumbar stenosis can present as radiculopathy. This usually refers to symptoms on one side if the symptomatic narrowing occurs in the spine’s foramen, which is where the nerve leaves the spine. Lumbar radiculopathy can feel like pain, weakness, and altered sensation into a leg. It can occur on both sides if both foramina on the same level are involved.

If the lumbar spine’s central canal is narrowed and symptomatic, there can be accompanying vascular compression, which affects the nerve’s blood supply (not the leg’s blood supply, that’s another different term). In this case, you may experience neurogenic claudication, which is slightly different than radiculopathy. Here’s why.

Expanding on Neurogenic Claudication

If the spinal canal is compressed due to stenosis, you may experience neurogenic claudication.

This symptom often feels like weakness, burning, or numbness into both buttocks and legs. It often feels worse with standing or prolonged walking and improves when you sit down or hunch forward.

You will notice that walking uphill, biking, and using a grocery cart in the store help to decrease your symptoms during activity. You almost never have symptoms when you’re seated. That “flexed” spinal posture gives your nerves a break and lets them breathe.

If you’re not sure if this is what you’re experiencing, you can easily test this yourself. Compare how you feel walking on a flat path to an uphill path. Which feels better?

If the uphill path decreases your symptoms (or gives you no symptoms at all), you may have neurogenic claudication on flat ground.

This is a detail that is helpful to note when you visit your doctor and/or physical therapist. It can help better diagnose your condition.

Types of Lumbar Stenosis and Treatment Implications

Physical therapists do not interpret imaging (radiologists have that power), but we can help you understand how the results relate to your treatment plan.

More often than not, your physical therapist’s treatment plan is already addressing related symptoms.

Here are some terms frequently used to describe “evidence” of your diagnosis in imaging, how they may present, and how your physical therapist is addressing this.

Foraminal Stenosis

When the nerve leaves the spinal cord, it enters the foramen of the vertebrae. The foramen is the opening where the nerve leaves the spine to travel towards the limb.

If this area is narrowed, then it’s called foraminal stenosis or lateral recess stenosis. They are often interchangeable because they refer to the same general area.

This type of finding alone usually correlates with radiculopathy down one leg. Closing down this space makes it worse (like side bending towards that side) and opening up the space makes it better (like side bending away from that side).

It is possible to have both foramina at one spinal level affected at once, which is called bilateral foraminal stenosis. One side could be symptomatic while the other is not, or they could both be symptomatic.

One way your physical therapist is addressing this is with stretches that help open the foramen to relieve pressure and inflammation of the irritated nerve root.

Central Stenosis

Your spinal column has a large canal where the spinal cord travels. It goes from the brain to the low back and buttocks.

If the lumbar level of this area has narrowed, it’s called central lumbar stenosis.

This type of finding alone usually correlates with neurogenic claudication. Standing and prolonged walking can increase symptoms and sitting can decrease symptoms. It is possible to have this with foraminal stenosis.

Your physical therapist has likely picked up on this presentation pattern by listening to your history and watching your postural preferences. You may be doing exercises that relieve pressure and inflammation while improving extension tolerance to help you do everyday activities with less symptoms.

Ligamentum Flavum Thickening and Osteophytes

The ligamentum flavum is a ligament between vertebral segments that sits behind the spinal cord. If it has thickened, it can make the spinal canal narrower. This is an age-related change that occurs over time.

You can see it below (kind of, it likes to hide). It sits in the back of the spinal canal and protects the spine from excessive forward bending.

- Ligamentum Flavum (highlighted)

Images courtesy of Complete Anatomy

The presence of osteophytes, or bony growths, can also take up room in openings of the spine. They’re also often associated with aging and don’t always contribute to your specific presentation. But sometimes, it can.

Conservative treatment doesn’t necessarily change due to these findings, as this bottom line still holds true: There is narrowing space causing nerve irritation, and symptoms go away when that space is opened.

So How Do I Address My Lumbar Stenosis?

Your treatment can be nonsurgical or surgical. Most people try nonsurgical (conservative) care first to avoid surgery, because you often can.

As mentioned, physical therapy is one of the most common nonsurgical ways to manage or decrease symptoms. Physical therapists can’t undo structural changes, but they can demonstrate ways to decrease inflammation and improve movement patterns that may be contributing unnecessary stress on the low back by strengthening areas like the legs.

- Do This! (Use your legs!)

Lumbar stenosis develops over time. So, you should expect a longer healing timeline. Changes don’t always occur immediately, but your physical therapist may have some tricks up their sleeve to help relieve acute irritations that contribute to chronic pain. It’s important to be consistent with exercises that feel good, even if your physical therapist isn’t around.

But, if your symptoms are severely impacting your quality of life and causing safety concerns (leg buckling, falls) due to major nerve involvement, your doctor may suggest surgery.

The aim of surgical intervention is to open the space by changing the structure. This could include removing or thinning out any structure that is causing excessive compression on nerve or spinal cord. If you are a candidate for surgery, ask your doctor if you have questions regarding the surgical procedure.

You’ll likely visit physical therapy as you recover from your surgery.

Reach Out!

Don’t be discouraged if you’ve been diagnosed with lumbar stenosis, regardless of the imaging evidence. Be proactive and see a physical therapist at JACO Rehab to address symptoms now!

Sources

1. Turk, D. C., & Wilson, H. D. (2010). Fear of pain as a prognostic factor in chronic pain: conceptual models, assessment, and treatment implications. Current pain and headache reports, 14(2), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-010-0094-x

2. Bussières A, Cancelliere C, et al. (2021) Non-Surgical Interventions for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Leading To Neurogenic Claudication: A Clinical Practice Guideline. The Journal of Pain, 22(9), 1015-1039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2021.03.147

3. Munakomi S, Foris LA, Varacallo M. Spinal Stenosis And Neurogenic Claudication. (Updated 2022 Feb 12). StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430872/